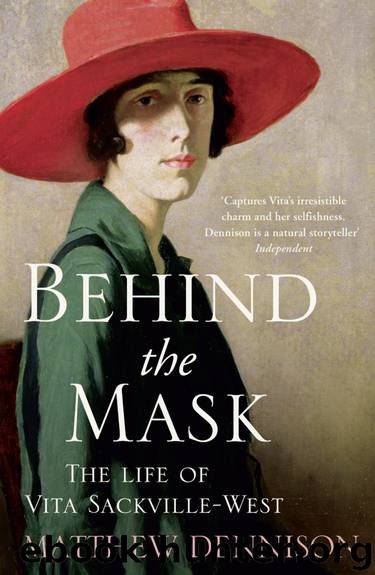

Behind the Mask by Matthew Dennison

Author:Matthew Dennison [Dennison, Matthew]

Format: epub

Published: 2016-11-06T23:00:00+00:00

PART V

The Land and the Garden

‘The deepest roots of all are those one finds in one’s own home, among one’s own belongings.’

Vita to Ben Nicolson, 25 March 1932

‘IT WAS THE Sleeping Beauty’s castle with a vengeance, if you liked to see it with a romantic eye; but if you also looked at it with a realistic eye you saw that Nature run wild was not quite so romantic as you thought,’ Vita wrote in the autumn of 1950.1 Her subject was her home of two decades, Sissinghurst Castle.

Vita first saw Sissinghurst on 4 April 1930, with Dorothy Wellesley, whose land agent Donald Beale had alerted her to its sale, and a thirteen-year-old Nigel. It goes without saying that she saw it with a romantic eye. April habitually inspired Vita to eulogy. It was the month when the Kentish country, ‘my own county’, looked ‘absurdly like itself’: ‘Cherry, plum, pear and thorn whiten the orchards and the hedgerows; lambs frolic; the banks are full of violets and primroses; the whole landscape displays itself as an epitome of everything fresh and innocent.’2 Vita had recently bought four new fields at Long Barn; she had also learnt in March of a threat to Long Barn’s privacy in the form of a proposed chicken farm on land immediately adjacent.

There was nothing fresh at Sissinghurst in the meagre sunshine of that April afternoon: it was cold and muddy and wet. It had been for sale for two years: the rot had set in long before. In an instant, Vita fell ‘flat in love’. ‘Contact with beauty, for me, is direct and immediate,’ she wrote.3 Transfixed by a tower of pinkish Tudor brick, ‘like a bewitched and rosy fountain [pointing] towards the sky’, she told a sceptical Nigel that here was somewhere they would be happy.4 She telephoned Harold ‘to say she [had] seen the ideal house – a place in Kent near Cranbrook’, some twenty miles from Long Barn and Knole.5 For the simple reason that she did not see it like that, she did not describe to him with any accuracy the two tired cottages, the tower shorn of the adjoining buildings it had once adorned, the entrance arch with its shabby flanking ranges, the rusty bicycles and iron bedsteads that choked the moat, the woodland dark and overgrown. Her affections would never waver.

Vita was in a mood to fall in love with Tudor ruins. The emotional tumults of the last decade were fleetingly quelled; in her romantic life she had achieved stasis, a moment of calm. In all her relationships – with Violet, Dottie, Virginia, Mary and Hilda – intoxication lay behind her; Geoffrey Scott had died of pneumonia the previous August, alone in New York. Her attachment to Virginia ran deepest. Now, as she had written to Mary in a different context, Vita had begun to crave privacy above all: she described it as constantly under attack from ‘myriads of noisy urgencies’.6 ‘I shun all voices, shrink from every task,’ Vita had written in a sonnet to Mary included in King’s Daughter.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26603)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17412)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16028)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15355)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14075)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12392)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8999)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8927)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7671)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7581)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6207)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5448)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5382)